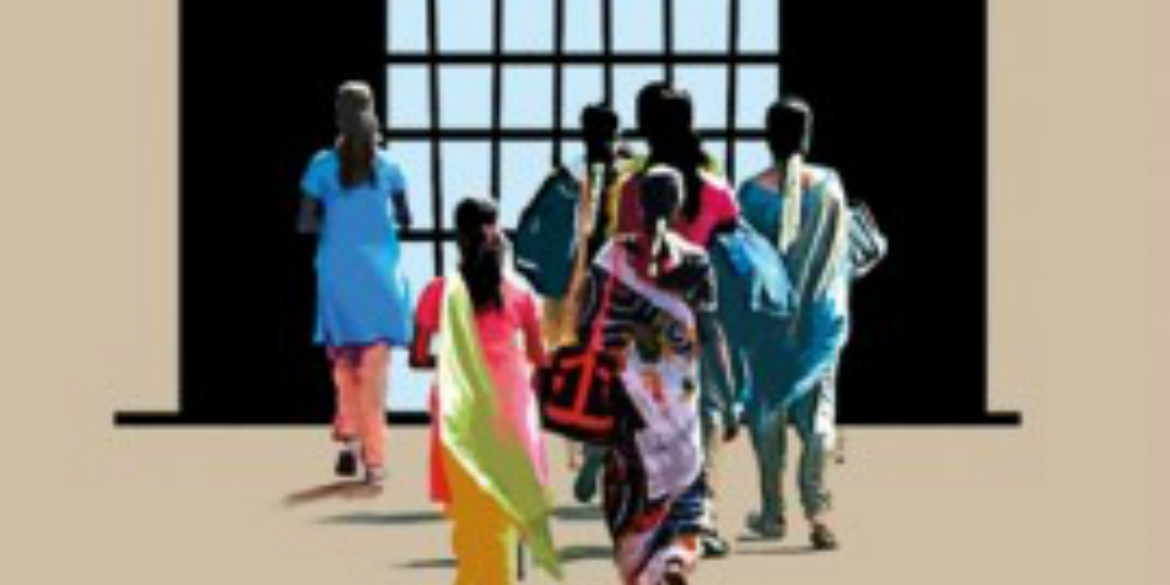

‘Flawed Fabrics’ – a new report by the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) and the India Committee of the Netherlands (ICN) – shows that workers are still facing appalling labour conditions that amount to forced labour in the export-oriented Southern Indian textile industry. The women and girls who work in the spinning mills of Tamil Nadu, some as young as 15, are mostly recruited from marginalised Dalit communities in impoverished rural areas. They are forced to work long hours for low wages. They live in very basic company-run hostels and are hardly ever allowed to leave the company compound. The researched spinning mills have Western companies and Bangladesh garment factories among their customers, including C&A, Mothercare, HanesBrands, Sainsbury’s and Primark.

The report portrays the situation in five spinning mills in Tamil Nadu, which is a major hub in the global textile and knitwear industry: Best Cotton Mills, Jeyavishnu Spintex, Premier Mills, Sulochana Cotton Spinning Mills and Super Spinning Mills. The research is based on in-depth interviews with 150 workers combined with an analysis of corporate information and export data regarding the companies involved. Spinning mills in this region produce cotton yarn and fabrics, both for further processing in the Indian garment industry and for export to other countries, in particular Bangladesh.

The teenage girls and young women told researchers how they had been lured from their home villages with attractive promises of decent jobs and good pay. In reality, however, they are working under appalling conditions that amount to modern day slavery and the worst forms of child labour. Workers don’t get contracts or payslips. Workers have nowhere to go to express their grievances. In the mills there are no trade unions or functioning complaint mechanisms. One interviewed worker at Sulochana Cotton Spinning Mills said of her living conditions: “I do not like the hostel; there is no entertainment and no outside contact and is very far from the town. It is like a semi-prison.”

Two mills were found to be supplying Bangladesh garment factories that fall under the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety. As such the report presents a direct link between the Accord’s signatories and unacceptable labour rights violations in India. Due to a lack of transparency in the garment sector, SOMO and ICN could not establish which signatories, All Western retailers and fashion brands, source from these factories. The export data also link the investigated spinning mills to three foreign banks: Standard Chartered Bank, The Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi and Raiffeisenbank. These banks provide financial services to the spinning mills and their customers. However, referring to banking security and privacy, the banks refused to disclose any details.

In the past few years, brands and retailers sourcing from Tamil Nadu have started to step up audits and corrective actions plans at the level of end-manufacturing units (first tier suppliers). However, only a small number of brands and retailers have started mapping and to some extent auditing their second-tier suppliers. The vast majority of buyers do not engage in monitoring and corrective actions at the level of the spinning mills (which are second-tier suppliers). Two of the researched mills received a certification (SA8000) for adhering to international labour standards, while this report shows labour conditions at these mills are far from acceptable.

SOMO researcher Martje Theuws says: “Business efforts are failing to address labour rights violations effectively. Corporate auditing is not geared towards detecting forced labour and other major labour rights infringements. Moreover, there is a near complete lack of supply chain transparency. Local trade unions and labour groups are consistently ignored.”

In addition, ICN programme officer Marijn Peepercamp states: “Governments at the buying end of the supply chain are failing to ensure that companies live up to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The state duty to protect and the corporate responsibility to respect human rights as laid down in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights are not being respected.”

The authors of the report, SOMO and ICN, call upon all corporate actors along the global garment supply chain – from spinning mills to fashion brands – to be more transparent about their supplier base. They have to be more ambitious in detecting and addressing human rights violations by allowing trade unions and civil society organisations to play their specific roles. In addition, buying practices (including pricing) need to allow for decent working conditions so that girls and young women in Tamil Nadu no longer have to face appalling working conditions that are tantamount to forced labour.

>> Download the report Flawed Fabrics (pdf)